ESSAY

MOTHER NATURE’S SONS

How the Beatles regenerated after the split

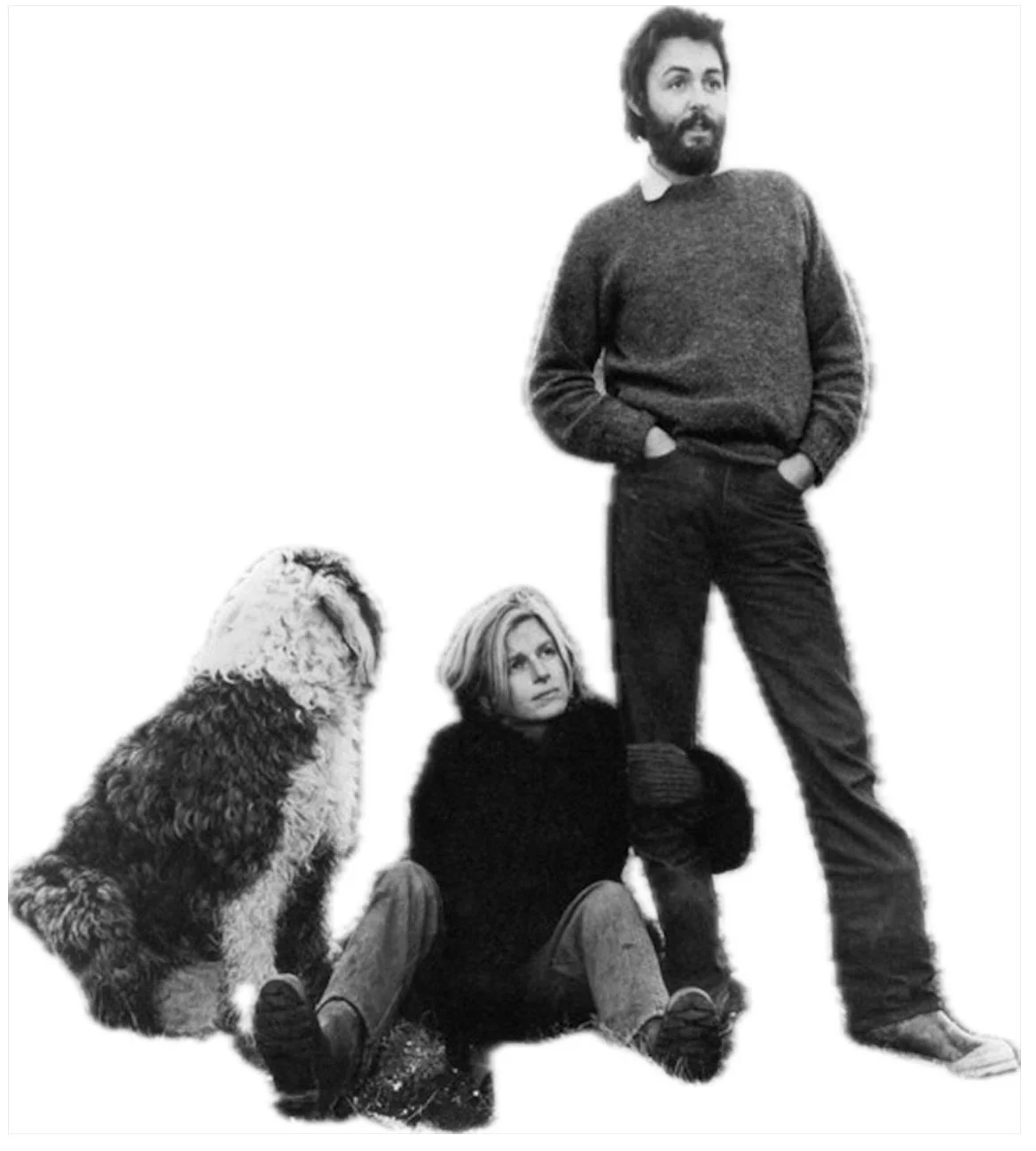

Around the time of the break up, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison moved closer to the countryside. David Rea looks at how their new homes impacted their album artwork and wonders how far they influenced their solo music.

1 September 2025

Photo: Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy Stock Photo

IT’S A LONG JOURNEY home from the end of the 1960s. In the final summer of that decade the four Beatles met at the studio for the last time to discuss the sequencing of Abbey Road. Around the time of the band’s break up, its principal songwriters Lennon, McCartney and Harrison moved into new homes. McCartney headed north to a 183-acre farm in the Kintyre Peninsula in Scotland, Harrison bought Friar Park, a 25-bedroom mansion set in 32 acres of land in Henley-On-Thames, and Lennon Tittenhurst Park, a Georgian mansion set in a 72-acre estate near Ascot.

McCartney’s new home consisted of a windblown three-bedroom farmhouse and outbuildings, but Harrison’s and Lennon’s were befitting of country squires; their decor and landscaping recalled a certain madcap English eccentricity. At Harrison's Friar Park the monk’s face light switches, the gargoyles, parapets and towers, the caves and grotto linked by waterways and decorated by warped circus mirrors variously recalled the fantastical worlds of Lewis Carroll, J.R.R. Tolkien and Roald Dahl. Inspired by the stories of Robert Lewis Stevenson, John Lennon insisted on having an island in Tittenhurst Park’s lake and had the car he had crashed the previous summer positioned on a plinth, still with his and Yoko Ono’s blood on the interior.

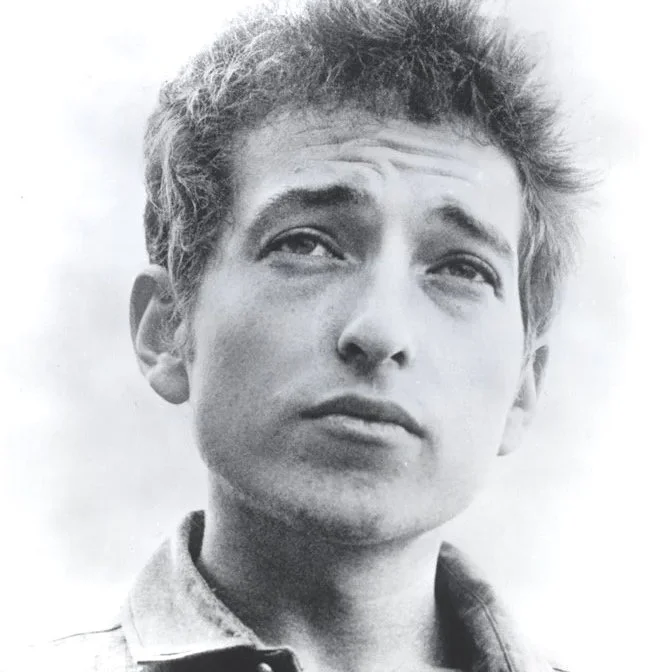

Lennon, McCartney and Harrison’s moves formed part of a broader migration of artists away from the city and closer to nature in the second half of the 1960s and the early 1970s. Laurel Canyon, where a vibrant artist community of Joni Mitchell, Frank Zappa, Jim Morrison and others flourished, might have only been an LA neighbourhood, but with its flowering hillsides, winding roads and birdsong it was a bucolic village in all but name. On the other side of America, Bob Dylan and Van Morrison moved closer to another celebrated artist community in Woodstock, set in the soft folds of the Catskill foothills. In 1970 Led Zeppelin spent time in a Welsh cottage called Bron Yr Aur, writing the songs for their third studio album and Donovan purchased three remote Scottish islands with the proceeds from his third LP, Sunshine Superman. The Scottish Bob Dylan planned to establish an artist commune on his new land, but others simply wanted sanctuary from press and fans, a place to bring up their families or space to compose.

These artists were also influenced by a broader cultural undercurrent. When Joni Mitchell sang ‘we've got to get back to the garden’ in her generational anthem, ‘Woodstock’, she was invoking an idea widespread in the late 1960s. In the face of unsettling technological advances and the threat of nuclear annihilation, the unspoilt countryside of America and Britain became visions of pre-industrialised innocence, where child of nature hippies could be at one with the birds, meadows and trees. But music royalty’s acquisition of such property was also driven by a desire for the very things the counterculture rejected: status and wealth. Members of The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin bought lavish properties in the leafy home counties, becoming neighbours with the country’s Tory-voting bankers and business owners. For Lennon, McCartney and Harrison, whose songs had variously celebrated hippy ideals from ego death to communion with nature, their new homes were sound investments for their sizeable fortunes.

“As they paired away the layers of artifice in their recording so they paired away their Beatles’ guises. Coming out of a band with such a strong group identity, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison used their new homes to help forge their post-Beatles personas.”

PLACE CAN INFLUENCE creativity profoundly. Led Zeppelin’s Welsh getaway cottage Bron Yr Aur has been credited with influencing their slight left turn into a folkier sound on Led Zeppelin III. Van Morrison's album Moondance is suffused with Woodstock’s tranquility, most notably on the gem ‘Into the Mystic’. Bob Dylan’s retreat to Woodstock and family life moved his music from the bluesy rock of Blonde On Blonde to 1967’s partially acoustic, folk-infused John Wesley Harding.

The argument that the Beatles’ retreat to quieter, more out of the way homes led to the contraction of their musical production ambitions is tempting: They record Abbey Road in London, whose B-side is amongst the tricksiest stretches of music they ever made. Then, after breaking up and scattering to the countryside, McCartney produces a debut solo album that sounds so much like a DIY, home-recording project, it is subsequently credited as one of the first lo-fi indie records; Lennon meanwhile creates the emotionally naked John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band, with a bare-bones core band of Klaus Voormann on bass and Ringo Starr on drums.

Tempting, but the argument is too convenient and the dates don't align. Only the brand-new songs on McCartney were written in Scotland; the album was recorded in St John's Wood in London, the scaled-back production the result of recording on a four track in the McCartneys’ living room. The minimalist material for John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band didn't emanate from Tittenhurst Park’s pastoral calm either. It was in part written at the Primal Center in Los Angeles and recorded at Abbey Road in London. And then, of course, George Harrison’s first solo album All Things Must Pass went the other way entirely. If anything its grand, baroque production recalled Friar Park’s architectural flamboyance rather than its rustic acres.

Moving further from the city did, however, help McCartney, Lennon and Harrison pair away their Beatles’ guises. Coming out of a band with such a strong group identity, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison used their new homes to help forge their post-Beatles personas. The film ‘Imagine’ includes a famous sequence set in Tittenhurst Park’s vast white drawing room; John Lennon performs the documentary’s eponymous song about a world without political borders or possessions at a white grand piano, while Yoko Ono opens the curtains letting daylight in. Here is the man full of demons all at once full of dreams, idealised and almost sanctified.

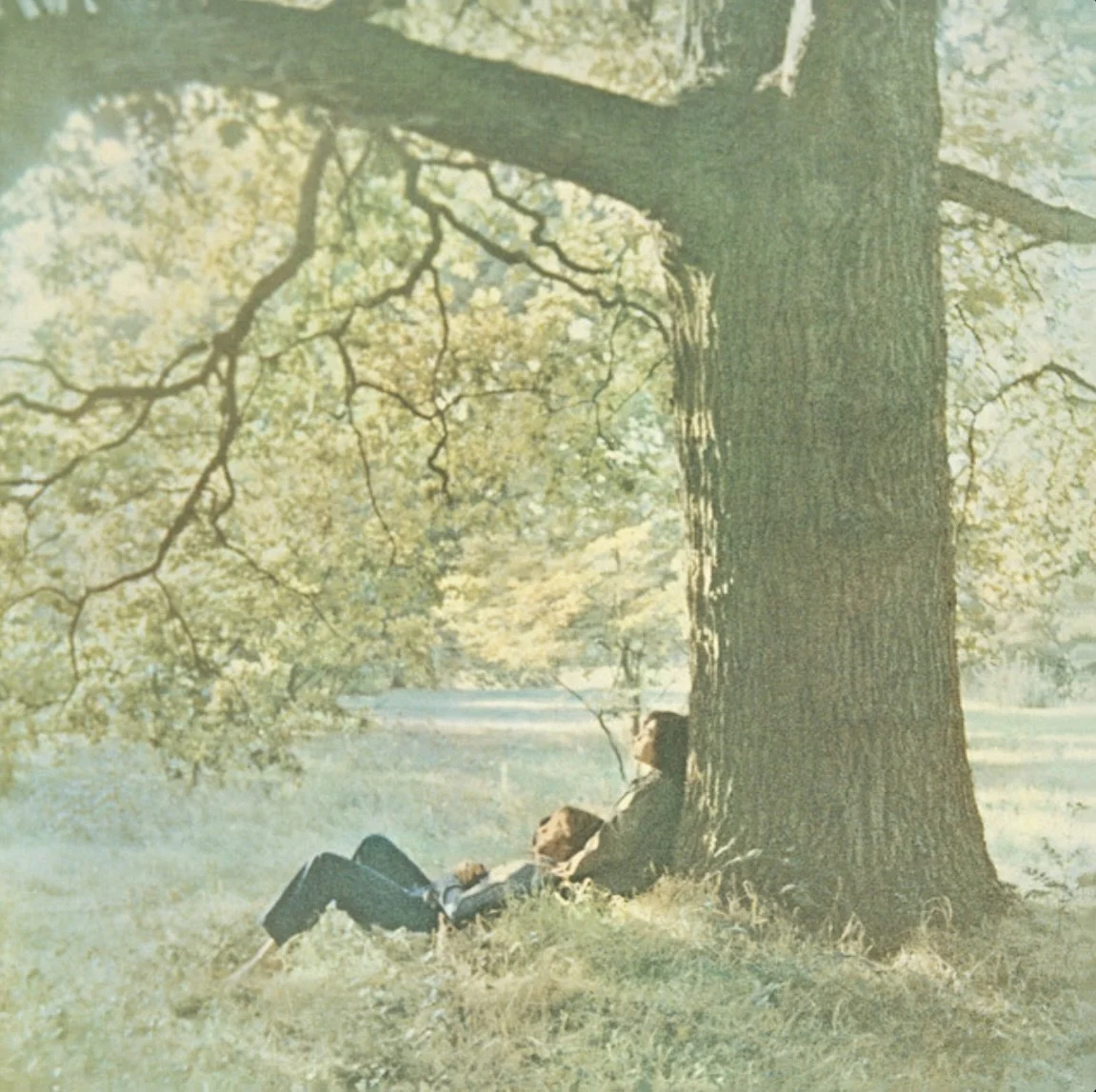

John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band

Cover Photograph by Dan Richter

Sleeve Design by John Lennon

It is striking the extent to which the Beatles’ new homes feature on their early solo album artwork. The cover of John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band shows Lennon and Yoko Ono at peace reclining against a tree in Tittenhurst Park, bringing to mind a sun-dappled Adam and Eve. For the cover of his second album, Ram, McCartney appeared on his Scottish farm in a plain white T-shirt, holding the horns of a ram; it couldn't have been further from the Beatle who wore a variety of brightly coloured jackets, ties and scarves in the video for ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’. It was a rejection of his dressed-up Beatles identity, as strident as Lennon's proclamation that he no longer believed in the Beatles in his song ‘God’. McCartney's Ram cover photograph presented the off-the-grid man of nature, strong enough to win a wrestling match with a sharp-horned ram. Widely blamed at the time for the break-up of the Beatles, entangled in the attendant legal mess and having received a critical mauling for his first solo album, it was the image of a man coming out fighting, virile, in charge.

Ram

Cover Photograph by Linda McCartney

Art by Paul McCartney

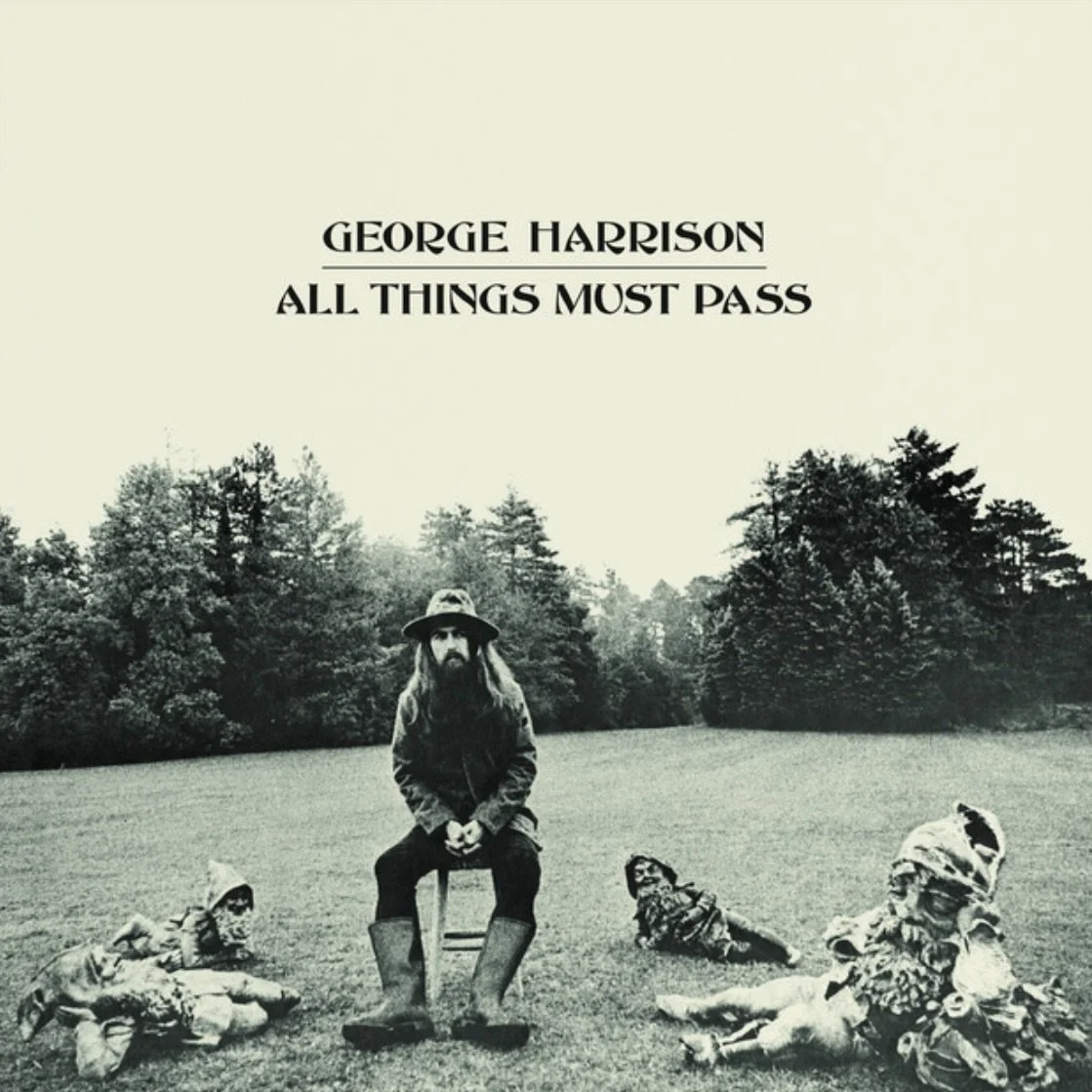

Packaged in a hinged box, Harrison’s triple album All Things Must Pass had a more tongue-in-cheek cover photo. The black-and-white shot showed George sitting on a stool in the grounds of Friar Park. In place of the trendy bright green trousers and glossy black coat he had worn for the 1969 rooftop concert at Apple Corps headquarters, Harrison now wore Wellington boots and a tatty hat, recasting the hip Beatle as a country bumpkin. At a time when everything the Fab Four did was exhaustively analysed, he chose to surround himself with four gnomes. That Harrison was both in the middle of and towered over these substitute Beatles possibly spoke of his anger at the way his songwriting had been sidelined and his artistic confidence now that he was finally free.

Cover Photograph by Barry Feinstein

Sleeve Design by Tom Wilkes

All Things Must Pass

The metropolitan, countercultural leaders who appeared on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s couldn't have been more different from the bumpkin, sheep herder and Adam with Eve who appeared on the covers of All Things, Ram and Plastic Ono Band. It was on those covers that, in the most idiosyncratic of ways, McCartney, Lennon and Harrison finally became mother nature’s sons.

© 2025 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

MORE ON THE 1960s

OPINION

by David Rea

25 October 2025

22 November 2025

ESSAY

20 September 2025