‘The Sixties are our heritage’: How the Jam invented Britpop’s ethos

ESSAY

Critics couldn't take the Jam seriously at first, claiming they were just a bunch of gimmicks. But their ‘hail your heroes’ ethos was entirely authentic, setting the blueprint for Britpop two decades later.

20 September, 2025

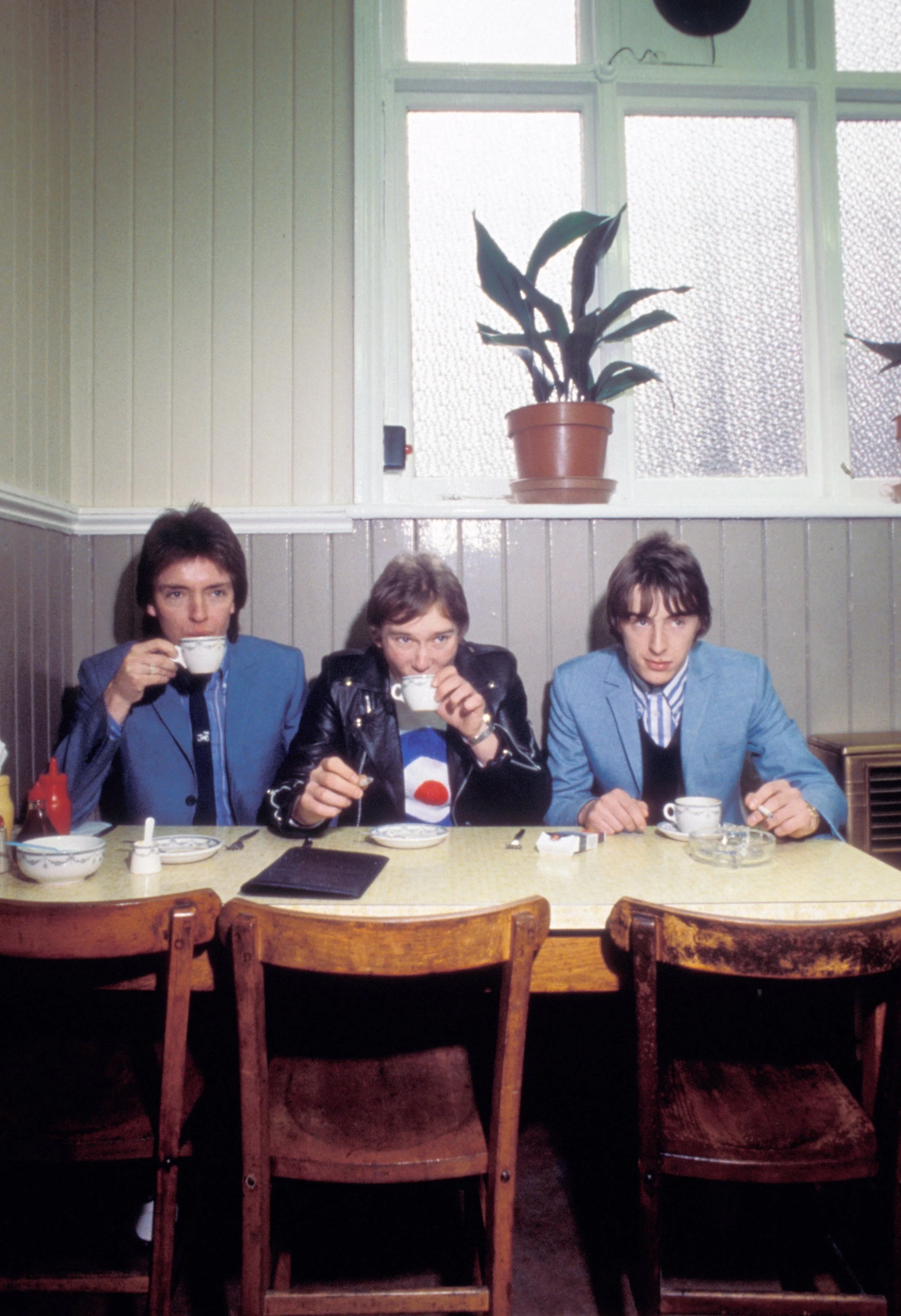

Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

Davidwr

AFTER HEARING the Jam’s debut LP In the City in the late spring of 1977, many concluded the group were a collection of gimmicks. Of a piece with the broader cynical response, a BBC journalist asked the band in July of that year: ‘How much of what you're doing is a mickey take? You’ve got the early sixties image and you play tracks like the Batman theme.’ There was a beat-length pause before Rick Buckler’s frosty reply: ‘There’s no mickey take really’. It was clearly going to be another uncomfortable interview for the emerging three-piece.

There was some justification for the accusation of parody. The ‘Batman Theme’, track six on the Jam’s In the City, had also appeared on the Who’s 1966 album, A Quick One. The Jam's debut album title had been a Who B-side and the title track had precisely the same ‘the kids know where it's at’ spirit as the Who’s ‘My Generation’. If you put the two bands’ debut albums on shuffle, the only discernible difference at certain points seems to be Roger Daltrey singing in a shiny American accent and Paul Weller in a commuter belt bloke snarl.

The BBC journalist continued, trying to slot the Jam somewhere into 1977. ‘I've been reading recently that, the opposite of the Sex Pistols, you support the Queen.’ You could almost hear the crackle in the air in the silence that followed. ‘No we don't support the Queen,’ Paul Weller replied. The interviewer ploughed on, asking which punk bands had influenced them. ‘None, I shouldn't think,’ Weller answered.

The reality was that punk and mod music shared at least some of the same influences. From across the pond, punk took something from MC5, the Velvet Underground and the Stooges, and mod from Detroit's Motown, Stax Records and Atlantic Records. But the sound of both could also be traced to the Shel Talmy-produced songs of the Kinks and Who. As far as the Sex Pistols and the Jam were concerned, the clearest dividing line was the Pistols wanted to burn down the past and the Jam resurrect it.

A few moments later the journalist circled back to the accusation of parody and asked his most cutting question. ‘Aren't you worried… you’re… copying ideas from a decade ago?’ And then, very quietly and pithily, Paul Weller reframed the idea of influence. ‘No we are not copying ideas, we are using ideas,’ he said. ‘It's part of our heritage, you know.’

‘It's part of our heritage.’ From kitchen sink drama to bands of the British invasion, 1960s influences were washing through the new wave of the late 1970s. More conspicuous examples included the Pretenders covering the Kinks’ song ‘Stop your Sobbing’, and Chris Difford lifting the title of Squeeze’s ‘Up the Junction’ from the BBC One Wednesday Play, a gritty piece of social realism first broadcast in 1965. But for these groups the 1960s provided influences, which they sometimes wanted to downplay; for the Jam the decade was an inheritance to be proclaimed. The ethos felt brand-new: Hail British music heroes. Claim your cultural past.

The Jam’s mentality was bound up with the mod revival they espoused. Paul Weller's Rickenbacker guitar, Lambretta moped and the music of the Who had all been part of the subculture’s first iteration, which the 1970s rebirth celebrated. Same subculture but different decade. By the late 1970s the mod revival’s natty threads and propulsive beats were out of key with the country. After the invigorating cultural explosion in the 1960s, Britain had become a tired and threadbare place, clapped-out and exhausted. There was widespread youth unemployment, the British government had to go to the IMF for a financial bail out and some were claiming that the unions were not only holding the nation to ransom but hijacking British democracy. Having gained connotations of cool a decade before, the Union Jack had been hijacked by fascists. ‘There ain’t no black in the Union Jack, send the bastards back,’ rang out from football terraces and gangs of skinheads. It wasn't long before the Jam’s mod aesthetic got caught up in the politics. Claiming they would vote for the Conservative Party and festooning their stage with Union Jacks was enough for the British music papers to label them right-wing. ‘We are against things like fascism and communism,’ Paul Weller clarified. ‘But I don't want to get too involved in direct politics. The important thing is the music.’

“From far away, it could almost be Supergrass impersonating Blur standing amidst the detritus of some Oasis debacle, in which Liam Gallagher has got into a drunken fight with the band’s merchandise stand.”

By the 1990s, it wasn't just the Jam claiming their cultural inheritance from the 1960s, it was future prime minister, Tony Blair. Before presenting the evening’s final statuette at the 1996 BRIT Awards, he said: ‘it has been a great year for British music… and at least part of the reason for this has been the inspiration that today’s bands can draw from those who have gone before. Bands in my generation like the Beatles, the Stones, the Kinks…’.

Tony Blair wasn't alone. By then, associating yourself with the music and fashion of the 1960s had become the thing to do. And unlike the Jam’s 1977 BBC interview (aren't you worried you’re copying ideas from a decade ago?), some journalists were trumpeting the trend rather than critiquing it. In August 1994, The Face magazine excitedly titled an interview with Noel Gallagher: ‘Never mind the Bollocks here’s the Sex Beatles…’. A year later on Channel 4’s The White Room, Damon Albarn performed The Kinks’ ‘Waterloo Sunset’ with Ray Davies, after which he turned, put his hands together and bowed towards his acknowledged idol.

In sharp contrast to the new wave of the late 1970s, britpop and the wider British cultural renaissance of the 1990s took place against the background of consistent economic growth. The cultural bandwagon everybody was jumping on was fuelled by the prosperity, helping to create borderline nationwide ebullience. The bandwagon was also a commercial juggernaut. Paint your guitar with a Union Jack. Put on a Union Jack-print dress a bit like the one Twiggy wore in the 1960s. Get that bloke from ‘Quadrophenia’ to do a vocal on your album. Make friends with Paul Weller. It was all part of a large-scale, media-driven cultural phenomenon, a glittering PR machine: Cool Britannia. But in 1977, the mod revival was too small to constitute a bandwagon. Jumping on it only made the Jam outliers.

Play a tune from the Jam’s debut album, look at the photographs of Paul Weller in a Fred Perry polo and the album artwork for the compilation Snap!, in which the Union Jack is draped over speakers. From far away, it could almost be Supergrass impersonating Blur standing amidst the detritus of some Oasis debacle, in which Liam Gallagher has got into a drunken fight with the band’s merchandise stand.

So what does that make the Jam? ‘Proto-britpop’, ‘new-wave-mod-revivalist-British-invasion-channelling punks’? Whatever. Look at Pennie Smith’s black-and-white photographs of the live shows, Paul Weller and Bruce Foxton in flight, legs twisted and sweat flying. Britpop tried to brandish 1960s British cool but too often only managed a sort of glossy pastiche. With their tough, authentic verve, the Jam not only did it first, they did it better.

© 2025 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

TAGS

PLAYLISTS

Lovingly curated song collections

I

I

I

RELATED

ALBUM REVIEW REWIND

ALBUM REVIEW REWIND