DYLAN AT THE CROSSROADS: How Bob Dylan's first single almost changed everything

Dylan's latest Bootleg Series instalment, Through the Open Window: The Bootleg Series Vol. 18 - 1956-1963, traces his arc from teenage rock 'n' roller to folk star. But had his first single ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ been a hit, things could have been very different. David Rea tells the story of what might have been.

22 November 2025

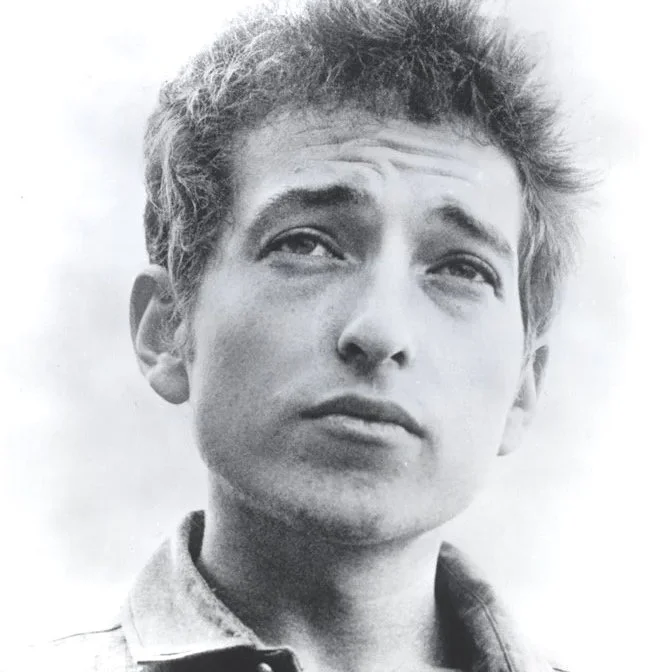

Photo: Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

IN 1956, a 14-year-old Bob Dylan gave a rock 'n' roll concert at his high school. According to eyewitnesses it was mortifying, sending shockwaves through the local community. This was Hibbing Minnesota, hillbilly country, where the icy winds blew in from the iron ore slag heaps on the edge of town, and the local radio station played Doris Day and Perry Como. On First Avenue miners drank cheap beer, the record store stocked Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire and behind drawn curtains families watched Name That Tune and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.

When Dylan appeared on stage, the then quiet loner had his hair done up in a Little Richard bouffant; when he imitated Richard’s infamous scream the audience laughed and the music was so loud the headmaster went backstage and cut the microphones. But even without amplification, Dylan continued to bash away at the piano, playing so hard that according to some he broke a pedal.

For an adolescent Dylan living in a humdrum town, 1950s youth culture held a magnetic allure. At the local cinema, his wide-eyed face was set aglow by James Dean’s brooding performance in Giant, and as Marlon Brando had led his motorcycle gang through California in The Wild One, Dylan rode his own out to a railway crossing on the outskirts of Hibbing and nearly collided with a passing train. Teenage Bob would listen to the radio beneath his bed covers late at night to muffle the noise, searching through the storms of crackle and hiss to find Elvis Presley and Bill Haley, Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf and Johnny Cash; he used his weekly allowance to collect Hank Marvin 78s and then Little Richard 45s. He even declared in his 1959 high school yearbook that his ambition was ‘to join the band of Little Richard.’

“The mood in the studio during the Freewheelin’ sessions was always going to be tense, taking place against the commercial disappointment of Dylan's debut album. But the pressure likely cranked up when it was suggested ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ should be backed by a band.”

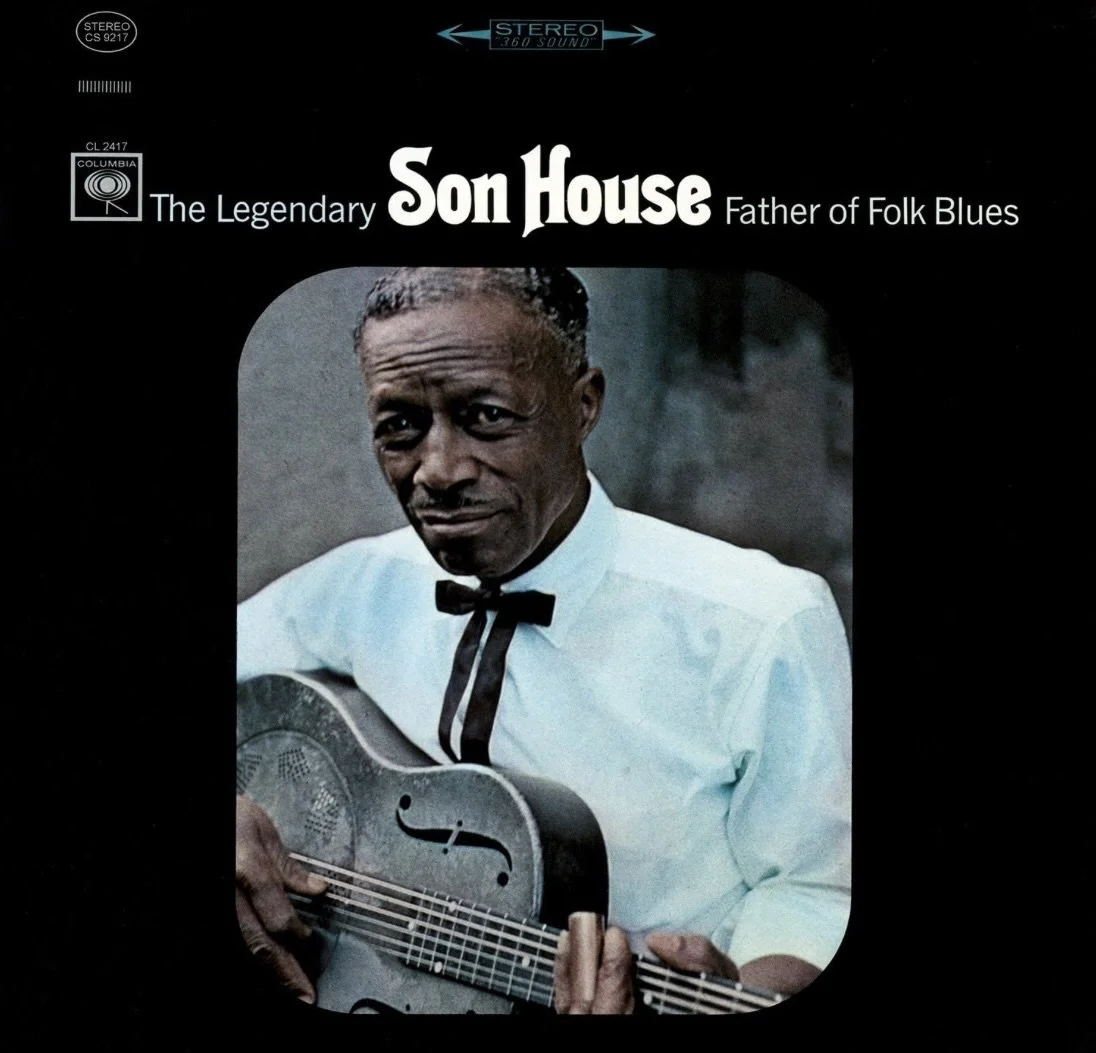

And then, seemingly all at once, Dylan switched allegiances to the wholesome hero of the American folk revival, Woody Guthrie. At first glance it couldn't have been more of a volte-face, but in reality Guthrie had more than a little in common with the rock 'n' roll rebel. The Hollywood archetype of the gunslinging Wild West cowboy greatly influenced the idea of American cool: the outsider who is outside the law, surly and free – able to go anywhere his horse will take him. A role model for the rock 'n' roll generation, Brando was a town cowboy in The Wild One who had exchanged a horse for a motorbike, and James Dean's disenchanted teenager in Rebel Without a Cause was a misfit rebel dying to belong. Guthrie had something of James Dean’s outsider and Marlon Brando’s outlaw. His scruffy appearance and rambling ways contributed to the prototype of the beatnik and hippie. A leading light in the politically radical American folk revival, he inscribed across his guitar: ‘this machine kills fascists.’ Rather than an about-face then, Dylan’s conversion from the likes of Little Richard to Woody Guthrie might more accurately be seen as a re-identification from one sort of countercultural hero to another.

Bob Dylan’s first single, the self-penned, two-minute and twenty-second rockabilly ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ was written around the time of the The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan recording sessions, possibly during a cab ride to Columbia Studios. It is something of an anomaly. The material on Freewheelin' surveyed a contemporary America of civil rights unrest, threat of nuclear annihilation and social injustice. But ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ turned to Dylan's interior world of emotional turmoil. Its feelings of confusion and alienation are an early iteration of the songs Dylan would write for Highway 61 Revisited, like ‘Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues’ and ‘From a Buick 6’.

The mood in the studio during the Freewheelin’ sessions was always going to be tense, taking place against the commercial disappointment of Dylan's debut album. But the pressure likely cranked up when it was suggested, possibly by producer John Hammond, that ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ should be backed by a band. Looking on was his manager Albert Grossman and a group of intimidatingly accomplished musicians. Dylan probably also felt deeply conflicted, pulled between his two personas to date: the adolescent rock 'n' roller who had nearly broken a high school piano, and the spotlit coffeehouse folksinger taking after Guthrie. Despite his conversion to folk music, he conceivably still harboured rock 'n' roll dreams. It wasn't so long ago that he had been excitedly fingering through rock 'n' roll 45s in Hibbing. During the takes for ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’, Dylan must have wondered who he was going to be. It was the mixed-up confusion of an identity crisis. No wonder that, after the 14th take, he stormed out.

“Had ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ been a hit, had Dylan plugged in for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, then several lines in the tree diagram of musical influence would have been redrawn at a stroke.”

The resulting single, which appears on the 2013 compilation Side Tracks, is a fascinating curio. It has two chords, a catchy hook and some memorable turns of phrase (‘… my poor feet don't ever stop… I’m hung over, hung down, hung up’), and is driven along by the horse-gallop rhythm of a Johnny Cash number. And then there is his voice. It is some distance from the great rock 'n' roll hurricane of Highway 61 Revisited, but it still has a strong wind blowing through it. You can also hear the conflict in the vocal too, however, the sound of a young man under pressure, uncertain, reaching to be somebody he hadn't quite become.

‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ was released as a single for Christmas 1962. It failed to chart. Artists’ fates are ever vulnerable to the vagaries of taste and happenstance. But had it been a hit, Columbia and Albert Grossman would surely have insisted the band come back to the studio and remain there, however many times Dylan walked out. The flop of his unplugged first album and the success of his band-backed debut single would have rendered that beyond question. And there is a good chance Dylan would have, eventually and perhaps reluctantly, gone along with it. He was, after all, at a crossroads, with a failed album behind him and the other roads of his future rapidly narrowing.

Had ‘Mixed-Up Confusion’ been a hit, had Dylan plugged in for The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, then several lines in the tree diagram of musical influence would have been redrawn at a stroke. True, some material on the album — ‘Girl from the North Country’, for example — would probably still have been backed by acoustic guitar, but we can imagine how others would have sounded with a full band: the deliberately paced, idealistic rage of ‘Masters of War’ recast as furious barnstorming rockabilly, the bright tabloid vignettes of ’Oxford Town’ gaining a darker edge, and ‘A Hard Rain’s A‐Gonna Fall’ becoming the first example of folk rock.

The legions of folk imitators like Peter, Paul and Mary might have taken a different course, or been partially erased from existence. The countless bands, from the Byrds to Fairport Convention, who stocked their albums with plugged-in versions of Dylan’s early folk songs would have been left with little to add. When George Harrison gave The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan to John Lennon, telling him it had ‘some vital energy’, it might not have inspired Lennon’s Dylan phase, which produced the introspective acoustic masterpiece, ‘You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away’. Would Paul McCartney's ‘Yesterday’ have been backed by an acoustic guitar? Would Donovan's ‘Universal Soldier’ now be accompanied by bass and drums? You could spend all day speculatively redrawing the forking lines of popular music genealogy.

As it was, the single failed. According to biographer Clinton Heylin, on returning to the studio after storming out, Dylan pulled the strap of his acoustic guitar over his shoulder and recorded an exquisite version of ‘Don’t Think Twice, It's All Right’. The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan made him, turning Dylan into the voice of his generation and a rebel with a cause. Two years later in 1965, he turned to a band-backed rock 'n' roll sound on the Chuck Berry-adjacent ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’.

The title of the accompanying album, Bringing It All Back Home, ostensibly pointed a finger at British bands who had appropriated music from America and then sold it back again. But the title also suggested something more personal. After the mixed-up confusion of the recording sessions in 1962, and a long detour through folk music, Dylan had returned to his first love, rock 'n' roll. He had come home.

© 2025 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

MORE FROM THE 1960s

OPINION

by David Rea

25 October 2025

MAKING A MASTERPIECE

By David Rea

18 October 2025