MAKING A MASTERPIECE

‘It took a unique kind of courage’: how Son House beat the odds to make a masterpiece

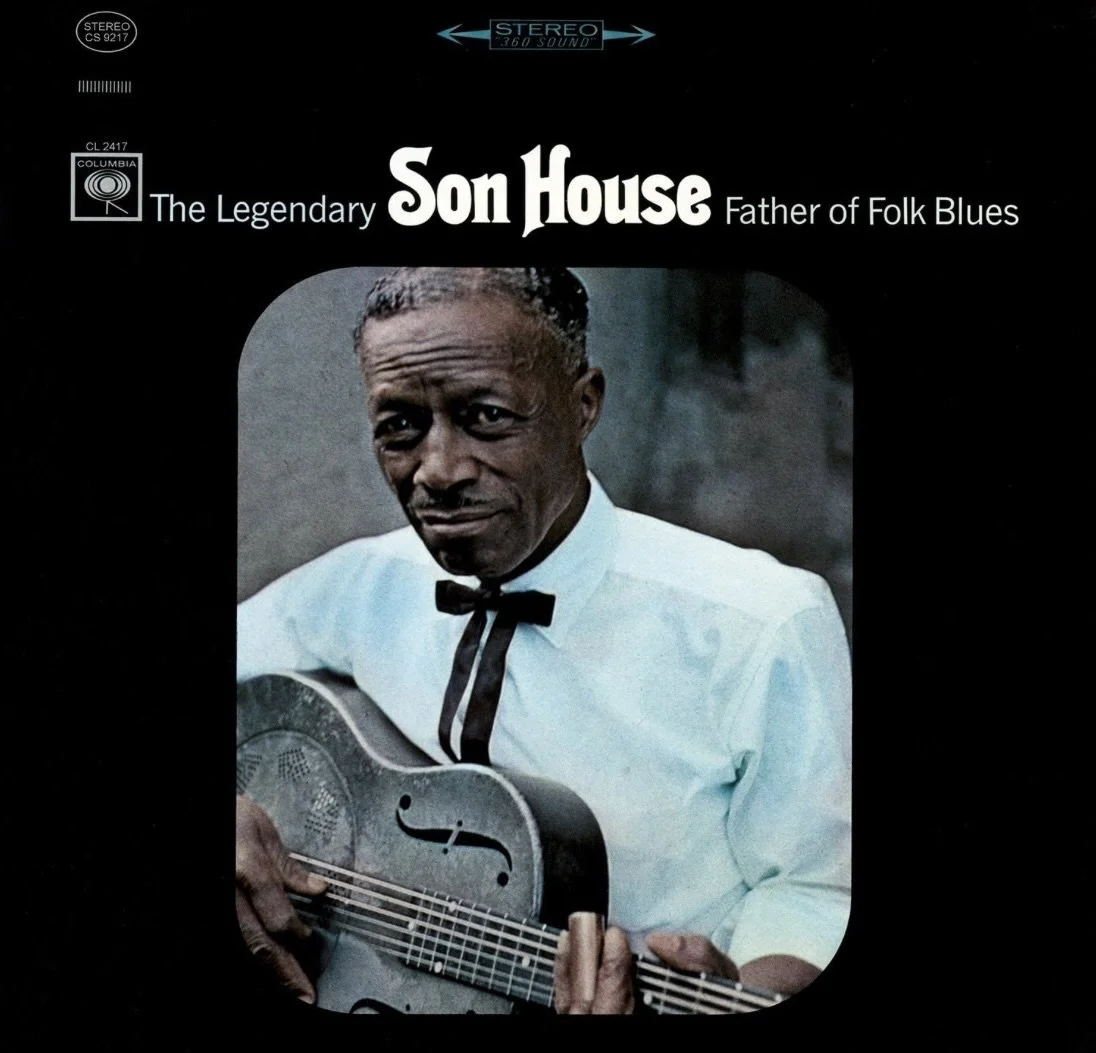

On the 60th anniversary of its original release, we look at how Son House made Father of Folk Blues for white America.

18 October 2025

Words mean more than what is set down on paper. It takes the human voice to infuse them with shades of deeper meaning. — Maya Angelou, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

WHEN SON HOUSE was found by young blues enthusiasts in 1964, he appeared a man out of time and out of luck. By then, one of the most significant figures in the Mississippi Delta blues story, was living with his wife in a retirement home, getting by on Social Security; he had cigarette-ash grey in his hair and deep lines in his face. Having calloused his guitar-playing hands with work at a foundry and on the New York Central Railroad, he had forgotten many of his music skills.

Back in 1930, House had recorded many of his country blues songs for Paramount Records, but then as Dick Waterman put it, ‘Music had to move, man. It had two jive, jump, step, plug-in-that-amp-baby, go go go!’ By the 1960s, with the forward-looking Civil Rights Movement and Black Power becoming part of the lexicon, young African-Americans had little interest in the weary defeat of the early country blues field recordings. They were drawn instead to brightly propulsive Motown and Black soul, to Nina Simone’s furious protest on ‘Mississippi Goddam’ and James Brown’s funky defiance on ‘Say It Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud.’

The shift in allegiances left bluesmen struggling for work; many retired from music, taking low-paid, blue-collar work. Keith Richards later claimed that when the Rolling Stones arrived at Chess Studios in Chicago in 1964, blues legend Muddy Waters was up a ladder with a paintbrush, and later helped the Stones lug their equipment around.

But as the blues was losing its first audience, another was growing, taking shape in the fallout from the atomic devastation in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Disaffected with leaders who had led them into a fearful Cold War, and tired of their parents’ staid conservatism, white youth subcultures were spreading across America. With a disposable income from a thriving economy, millions of teenagers went in search of alternative voices. For most that meant edgy rock 'n' roll, but on college campuses and a handful of urban areas it meant pre-war country blues. Soon a small underground scene was growing: collections of old blues 78s were amassed, blues record labels were started up, radio shows put on and small concerts organised. Others jumped in cars and headed south to track down the greats of the Mississippi Delta blues. Three of these young enthusiasts were Dick Waterman, Phil Spiro and Nick Perls. In June 1964, they got in a Volkswagen and drove almost 4,000 miles through sweltering heat in search of Son House, eventually finding him at 61 Greig Street in Rochester.

Such searches turned up a number of old African-American bluesmen, who were able to play a second act. Not for black audiences in the barrelhouses and juke joints of the Deep South or the clubs in Chicago, but for predominantly white crowds at the Newport Folk Festival and the American Folk Blues Festival Tour through Europe. Before long the American blues revival was in full swing. Through a misted coffeehouse window in Greenwich Village, one might have spotted John Lee Hooker playing before a small audience of beatniks, tourists and fellow performers, including the likes of Dave Van Ronk and Bob Dylan.

“After insisting on absolute quiet in the room, Hammond introduced the next take, ‘79148, Death Letter, take two,’ and then we hear Son House’s guitar, not partially masked in the crackle of old recordings, but clear and present.”

‘It took a unique kind of personal courage,’ Dick Waterman wrote of Son House’s decision to make a comeback. A lot of people helped along the way. Al Wilson, later a member of Canned Heat, steered him back through his old songs, and Waterman undertook his management. There was a story in Newsweek magazine and the first gigs at the University of Chicago, Indiana University and NYC. Waterman began a tireless search for a good quality recording contract, finally organising a meeting with renowned producer John Hammond in New York. House signed a contract with Columbia Records (then the most prestigious recording company in the world), agreeing to record one album. Sometime between the last of the snow melting in the late winter of ’65 — perhaps the first snow House had ever seen — and the first cherry tree blossom appearing in Central Park, House made his way to Columbia’s state-of-the-art studios to make what would become his most celebrated album. It was an extraordinary opportunity, but also most likely his last chance at commercial success.

‘We’d like absolute quiet in the room too please,’ Hammond announced early in the sessions, the snippet of speech caught on Father of the Delta Blues: The Complete 1965 Sessions. According to blues collector Lawrence Cohn, the studio had been made to look like a small club and more people were present than could fill a New York coffeehouse. If House felt the pressure, then he hid it well. This is not the sound of a man whose career was at a crossroads, who was being closely watched by a crowd, or listened to by a legendary producer. House had had more than adequate training for what he faced over those three days of recording. Playing the juke joints of the Mississippi Delta, raucous, drunken and sometimes dangerous places, he’d developed the skill of turning inward and drawing from a deep well of feeling, all while surrounded by noise and distraction. Somehow, in that crowded New York recording space, House managed to dredge up a palpably lonesome feeling.

After insisting on absolute quiet in the room, Hammond introduced the next take, ‘79148, Death Letter, take two,’ and then we hear Son House’s guitar, not partially masked in the crackle of old recordings, but clear and present. House’s slide scratching across the strings sounds like it has been summoned up from the depths of history, or the bottom of a whiskey bottle. Through the unadorned lucidity of Hammond’s production we feel Son House’s human presence as never before. It is as if he were on a chair playing right in front of us.

Then a voice cuts in. ‘Excuse me, Son,’ John Hammond interrupts, ‘I wanted the same number again [referring to ‘Death Letter’]’. House had mistakenly struck up what would end up being the album's closing track ‘Levee Camp Moan’. Maybe he had been nervous after all. House’s reply sounds weary and cautious: ‘The same one? Oh I'm sorry.’ In isolation it suggests a man who spent his life being deferential to white folk. But not according to Waterman. As he had it, House might have been ‘painfully polite’, someone who always said thank you when he signed an autograph, but he ‘was nobody's Uncle Joe’. Responding to a policeman who wrongly suspected him of casing beachfront houses in Malibu, Waterman recalls the way House spoke his mind, telling the officer in no uncertain terms the truth of the matter.

“The intensity of House's performances have sometimes been attributed to this interior battle between the boy raised in a religious household who ended up in prison for manslaughter, between the man who feared God but drowned his pain in corn liquor, the Baptist preacher who played the Devil's music. But House’s voice is more layered than that sacred-profane struggle posits.”

Listen to the exchange between John Hammond and Son House, and take two of ‘Death Letter’, here:

After Hammond's correction, House begins again, metamorphosing from humble old man into deep-souled bluesman as he launches into a spellbinding rendition of ‘Death Letter’. The drily twanging and pinging guitar strings bring to mind the heat haze of the Mississippi Delta’s cotton plantations and dishevelled shacks. What must House have looked like playing the song, alone on his steel-bodied National resonator guitar, in that state-of-the-art studio? Did he roll his eyes back in his head as the song transported him away, as he would do when playing in the Delta, and then blink as he finished the song, as if waking again into the present?

‘Death Letter’, the album’s eventual opener, tells an unrelentingly bleak story. A man receives a message that his lover is dead. He immediately set off to find her and, discovering her corpse, looks down into her face and reflects she will lay there till Judgement Day. The day after the funeral, he wakes at dawn and hugs the pillow she once lay on. That visceral evocation of death and chilling reference to Judgement Day (repeated several times in the song) introduces us to House’s fear-steeped faith, and one side of the central conflict of his life between the sacred and the profane. Opening side two, ‘Preachin’ Blues’ introduces us to the other side. ‘You know I want to be a Baptist preacher,’ he sings, before playfully quipping, ‘so I won't have to work.’ Here is the Son House who spent so much of his time drunkenly ‘barrelhousing’.

The intensity of House's performances have sometimes been attributed to this interior battle between the boy raised in a religious household who ended up in prison for manslaughter, between the man who feared God but drowned his pain in corn liquor, the Baptist preacher who played the Devil's music. But House’s voice is more layered than that sacred-profane struggle posits. Frayed and gravelly one moment, possessed and steely the next, slipping into falsetto for a note or two. Listening to this record is like peering into the depths of a Rembrandt self-portrait.

This album couldn't have been more out of key with mid-60s urban America of shiny mod cons and the futuristic space race. Released almost exactly two years after the assassination of JFK, and the year after the Civil Rights Act enforced equal voting rights and outlawed segregation in public places, it landed in 1965, in an America of tear gas-shrouded protests in Alabama, and buildings in Watts flame-blackened by riots.

If you want to get a sense of what it was like to be an African-American in the Mississippi Delta in the first half of the 20th century, when Son House first played these songs, you could look at old black-and-white photographs, watch a documentary or read Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. If you want to feel the consequences of that period of history, you can look at the news footage of those Watts riots, or listen to the Black soul of the era. If you want to understand both, you should search up Father of Folk Blues and press play.

© 2025 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

Listen to the take of ‘Death Letter Blues’ used on the finished album, and the White Stripes cover of the song, here: