‘Medical treatment may be advisable’: The British Elvis Presley Cliff Richard’s role in the story of punk

The British Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard, has been a national treasure for 60 years. But back in the 1950s, he had a dirty guitar sound and caused moral outrage, playing a role in the labyrinthine story of punk.

By David Rea

7 February 2026

Artwork and photos courtesy of: Denys Kalitnyk / Alamy; Denys Kalitnyk / Alamy; WS Collection / Alamy Stock Photo

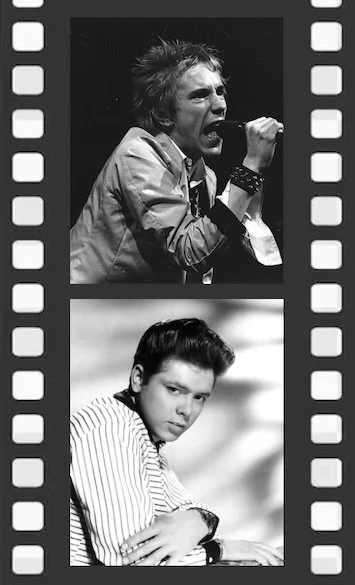

ON A CHILLY NIGHT in November 1976, not far from London's Leicester Square, passers-by could hear a muffled racket coming from a doorway. Down the stairs and out into a brightly lit circular basement, there was a raucous crowd and an amphetamine-fuelled atmosphere of violent threat. Two young women were dressed in bin-liners, tethered together with a dog chain. Another audience member was wearing a Cambridge Rapist mask. Cameras were everywhere, flashbulbs flickered, and journalists were carrying out interviews on the peripheries. Onstage, Johnny Rotten looked pale, half-feral, and emaciated; he had burn marks on his arms and he was staring at the audience with eyes glittering with anger. With little ceremony, the Sex Pistols launched into a riotous rendition of ‘Anarchy in the UK’, and the small audience became a stormy sea of wrestling limbs and flying beer.

If you wanted to tell the story of the first wave of British punk, that Sex Pistols gig in 1976 is as good a place to start as any. But punk’s larger story has more tangled origins. Trying to tease out its various strands is like trying to find several needles (or should I say safety pins) in a haystack. There was the scene at CBGB in Lower Manhattan, elements of Krautrock and the harder edges of late 1960s psychedelia; the Stooges, MC5, the Velvet Underground, and British garage rock bands like the Kinks and the Who. But before any of that, there was rock ’n’ roll, which probably foreshadowed punk more than any other music or subculture.

Let's look at an unremarkable point on rock ’n’ roll’s timeline, the 13th of September 1958, and focus in on the most unlikely artist to associate with punk, the British Elvis Presley, Cliff Richard. On his debut TV appearance on ITV’s Oh Boy!, when he performed what would become his first single, ‘Move It’, we can pick out several of the rock ’n’ roll seeds which grew into punk.

Across Britain, excited teenagers and agitated parents gathered around televisions to watch. Standing in the luminous circle cast by the spotlight, Cliff Richard waited, knowing a good performance could launch his career. Broadcast in black and white, it wasn't possible to see the pink of Richard's tailored jacket, tie and socks, which he had purchased for the occasion from Dean Street in Soho; it was equally difficult to see his make-up. ‘He was wearing so much eyeliner,’ an NME reviewer later reported, ‘he looked like Jane Mansfield.’ The television reception fizzed in and out, the picture warped, and frustrated teenagers held the aerial in various positions in vain attempts to catch the best signal. The guitarist struck up a blues lick before settling into the signature rhythm of rock ’n’ roll.

“Something of punk’s shock-tactic provocations can also be seen in Cliff Richard’s television debut. He shook his hips suggestively; he snarled his lips like Elvis Presley. It didn't spread moral panic like the Sex Pistols’ infamous TV interview on Today with Bill Grundy, but it was still met with thunderous disapproval.”

That guitar rhythm was straight-up Chuck Berry. But it was also, with a good deal more guitar distortion added in, the Ramones’ ‘Loudmouth’, and wasn't so far away from the Sex Pistols’ ‘EMI’. The influence of 1950s rock ’n’ roll guitar styles on punk has been exhaustively documented, but Chuck Berry summarised it best in his review of the Sex Pistols’ ‘God Save the Queen’ in Jetlag fanzine in 1980: ‘Guitar work and progression is like mine’.

The song Cliff Richard performed that evening, ‘Move It’, is arguably the first authentic rock ’n’ roll single made in Britain. TV producer Jack Good said it could have been produced at Sun Studios in Memphis. Its guitar might not have had the dirty fuzz of the Ramones, but it was well on its way. When ‘Move It’ was recorded at EMI's Studio Two in the summer of 1958, engineer Malcolm Addey let the needle swing into the red, helping to create a guitar sound which was compressed and crunchy.

Something of punk’s shock-tactic provocations can also be seen in Cliff Richard’s television debut. He shook his hips suggestively; he snarled his lips like Elvis Presley. It didn't spread moral panic like the Sex Pistols’ infamous TV interview on Today with Bill Grundy, but it was still met with thunderous disapproval. Despite Richard's puppy fat and angelic face, critics could only see sexual menace and vulgarity. ‘His violent hip-swinging was revolting, hardly the performance any parent could wish her children to see,’ the same NME journalist who had complained about his proto-punk eyeliner wrote. ‘If we are expected to believe that Cliff was acting naturally,’ the journalist continued, ‘then consideration for medical treatment may be advisable.’

For anybody who took the time to listen, the lyrics of ‘Move It’ also had the potential to shock. More than 30 years before the Buzzcocks’ ‘Orgasm Addict’ and X-Ray Spex’s ‘Oh Bondage! Up Yours!’, rock ’n’ roll (the term itself a euphemism for coitus) was already making tacit references to sex. Elvis Presley’s ‘Jailhouse Rock’ gave a nod and a wink to gay flirtation (‘Number 47 said to number 3 / You’re the cutest jailbird I ever did see / I sure would be delighted with your company / Come on and do the Jailhouse Rock with me’), and with its description of ‘greasing’ it so one didn't need to ‘force’ it, the original lyrics of Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’ provided sage advice for those wishing to try anal sex. Mild by comparison, ‘Move It’ nonetheless contained a trace of sexual innuendo: ‘Come on pretty baby, let's move it and groove it / Well a shake-a baby shake, oh honey please don't lose it’. (Britain’s rock ’n’ rollers seemed to be acknowledging the music’s sly eroticism with stage names which sounded a bit like porn stars’: Duffy Power, Vince Eager, Dicky Pride and Tommy Steele, to name a few.)

“Two decades before Covent Garden’s The Roxy Club was closed in part due to ongoing violence, the so-called ‘rock and roll riots’ broke out in Britain.”

Just like punk, 1950s British rock ’n’ roll had its fair share of violence too. The aggressively writhing sea of jiving bodies, in which flailing arms struck other dancers, was alarming, and from a distance didn't look so different from punk audiences violently thrashing around in what would later be called mosh pits. Two decades before Covent Garden’s The Roxy Club was closed in part due to ongoing violence, the so-called ‘rock and roll riots’ broke out in Britain. After watching Blackboard Jungle at a cinema in London’s Elephant and Castle — the soundtrack of which featured ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and the Comets — the press reported that Teddy boys went wild and committed vandalism. At cinemas showing the musical Rock Around the Clock in the same year, teenagers became so enthused they took to the aisles to jive, which escalated into violence and vandalism. After the film premiered in Manchester, The Daily Mirror reported that around 1,000 teenagers ran riot through the city. Later, John Lennon expressed dismay that similar aggression hadn't broken out when he watched Rock Around the Clock at a Liverpool cinema.

Violence also infiltrated Cliff Richard’s early live performances. At one show at the Trocadero in London’s Elephant & Castle, Teddy boys threw coins at the group from balconies. But this was one aspect of the era’s youth culture Cliff Richard wanted nothing to do with. ‘Those coins could have taken somebody’s eye out,’ he later complained in his autobiography, The Dreamer.

Following his performance on Oh Boy!, teenagers bought Cliff Richard’s ‘Move It’ in droves. It entered the charts at No. 12 and eventually peaked at No. 2. His career had well and truly begun. But it wasn't long before Cliff Richard moved into the mainstream. For a performer who went on to star in wholesome films such as Summer Holiday, became a born-again Christian in 1965 and was later knighted, it is easy to forget that he was once, in some quarters, viewed with fear and suspicion.

Did he have any direct influence on those who would later shape punk? Back in 1958, as the gritty rebellion of ‘Move It’ ruled the airwaves, the leaders of the first wave of British punk were mostly young children or toddlers, and those who helped create the proto-punk of 1960s British garage rock tended to cite American influences. Even if they had been influenced, they were unlikely to acknowledge it, given Cliff Richard's decidedly un-rock ’n’ roll status by the mid-1960s. What is certain is that, however brief his time in rock ’n’ roll, Cliff Richard’s Jane Mansfield eyeliner, outrageously swinging hips, the raw rock ’n’ roll sound of ‘Move It’, and his countercultural snarl all helped disseminate one of punk’s clearest blueprints: rock ’n’ roll.

© 2026 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

RELATED

ESSAY

20 September 2025

HOW THEY WROTE THE SONG

by David Rea

31 January 2026