Most of the Time

10.

from Oh Mercy

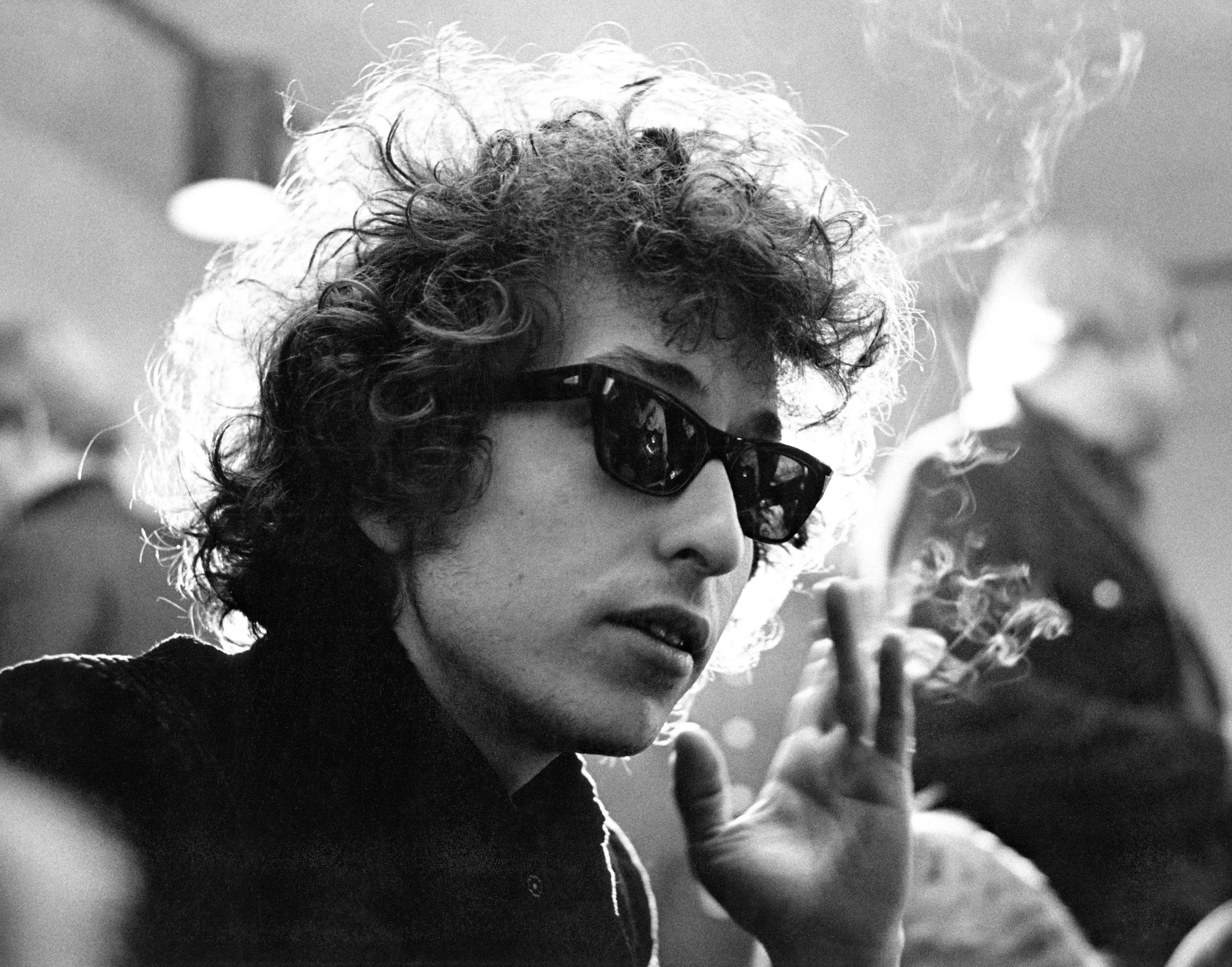

One night at Dylan's house sometime in the late 1980s, Bono asked if Bob had any new songs. Fetching pages from a drawer, Dylan showed him some recently penned lyrics. Bono read them over and suggested he record them; Dylan said they should be doused in lighter fluid. But Bono insisted. He picked up the phone, called U2’s producer Daniel Lanois and put Bob on the line. If you're ever in New Orleans, Daniel told him, you should look me up.

During the subsequent sessions for Dylan's 1989 Oh Mercy, ‘Most of the Time’ came together slowly and painfully. ‘It didn't have a melody,’ Dylan remembered in Chronicles: Volume One, ‘so I would just have to strum it ‘til I found one… Dan thought he heard something. Something that turned into a slow, melancholy song.’ What eventually came together was more than simply melancholy; it was the wistful evocation of an old lover’s ghost.

We never forget those we have truly loved. The vagaries of memory and distortions of distance leave a feeling of uncertainty, of something unresolved. What would it be like to see that special someone again? Dylan describes a life of getting by, with an air of vague contentment: ‘Most of the time / My head is on straight / Most of the time / I’m strong enough not to hate’. But the end of each verse circles back to the same person. ‘Most of the time… I can smile in the face of mankind / Don’t even remember what her lips felt like on mine.’

It seems unlikely Bono foresaw that Daniel Lanois’ trademark wall of sound would provide the perfect vehicle for Dylan's plaintive lyrics, but it did. The deep wash of sound evokes dreamy nostalgia, of something far away and out of reach, the sour guitar lines adding something bitter and doubtful. It is an emotionally potent mix. Oh Mercy’s closer, ‘Shooting Star’, explores a similar theme, but on ‘Most of the Time’ it is conveyed with a lighter touch and greater poignancy.

One Too Many Mornings

9.

from The Times They Are A-Changin’

The song captures the emptiness left by a departed lover, in this case Suze Rotolo’s months-long trip to Italy in 1962. Dylan sets the scene with well-selected details: a silent night in New York, Greenwich Village like a deserted film set, a dog bark echoing down an empty street. We can feel the ‘restless hungry feeling’ of a separation, the emptiness and defeat of a relationship towards its apparent end.

The guitar picking is feathery, the harmonica and voice little more than an exhausted whisper. Producer Tom Wilson draws out the song’s haunted mood with a touch of reverb. Dylan’s fingers slide up and down the fretboard, sweetening the bleakness; the scratch of his fingers on the fretboard captures the intimacy of the recording. Probably Bob Dylan’s most tender and exquisitely understated performance; he has never sounded so wounded or subdued again.

The song was rerecorded as a duet with Johnny Cash during the sessions for Nashville Skyline. The tape catches producer Rob Johnson introducing it with the incorrect title ‘A Thousand Miles Behind’. It’s unlikely such an intimate song about separation and loneliness would suit two voices, or have matched well with Johnny Cash’s rich baritone. Whatever the reason, the duet has never been released.

I Want You

8.

from Blonde on Blonde

One can feel the rush of Dylan's pen across the page in the torrent of images. The bells are cracked, the politicians are drunk and the mothers are weeping. Through the chaos of this disenchanted world comes a cry of yearning, a line as plainspoken as Dylan ever wrote during his plugged-in trilogy of 1965 and 1966: ‘I want you’.

The song was recorded over the course of four hours one early morning in March 1966. We can imagine the band playing in the Nashville studio through a dense fog of cigarette smoke. Dylan’s harmonica, Al Kooper's organ and Hargus Robbins’ piano combine into the poppiest iteration of the album’s ‘thin’, ‘wild mercury sound’, rattling along like an overloaded circus wagon. Al Kooper’s organ is a particular highlight, filling the narrow spaces with its ghostly notes.

According to Kooper, Dylan wasn't in any hurry to record the song. ‘I kept pressing [Dylan to record it] because I had all these arrangement ideas,’ he said, ‘and I was afraid [it] wouldn't get cut.’ But on the final night of the session, Dylan finally acquiesced. Alongside ‘Just Like a Woman’, this song’s accessible and incisive melody stands out from the rest of the album, and the song was released as a single in June 1966. It might also be seen as the little pop sibling of ‘Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands’, sharing the epic album closer’s aching desire.

I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight

7.

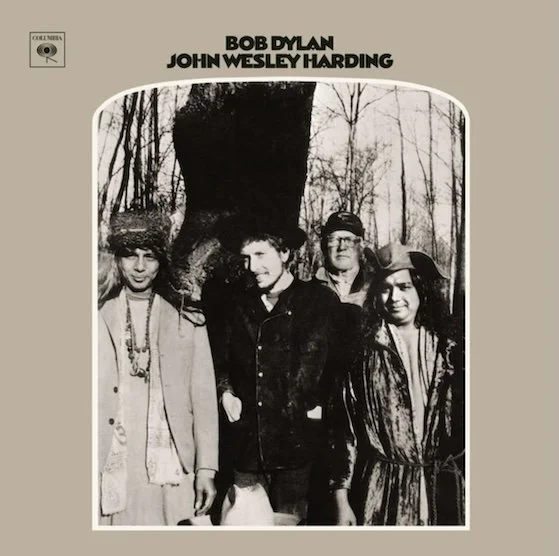

from John Wesley Harding

Amidst 1967’s widespread technicolour pageantry, John Wesley Harding sounded as monochrome as the album’s black-and-white cover photograph. It might have seemed almost contrarian to put it out in the same year as Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, Disraeli Gears and Axis: Bold as Love, but its folk tales were as playfully florid as any of that year’s psychedelia. John Wesley Harding was slightly out of step with Dylan’s own discography too, a reset of sorts after the foggy blues rock of Blonde on Blonde. But that folkier sound, like the black-and-white cover photograph and his retreat to Woodstock, was probably a deliberate move away from the limelight.

The album’s closing track, ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight’, was the most straightforward love song Dylan had written up to that point. Looking ahead to the country songs on Nashville Skyline, it is as warm, sweet and comforting as the singer’s suggestion of a romantic night in: ‘Kick your shoes off, do not fear / Bring that bottle over here / I’ll be your baby tonight’. (Although, the invitation to ‘close your eyes, close the door’ would probably have resulted in a few bumps and bruises, spoiling the romantic atmosphere!)

Dylan has always had an uncanny ability to write wholesome, homespun tunes with timeless appeal, from ‘Make You Feel My Love’ to ‘Lay Lady Lay’; they crop up in his discography like perfectly crafted anomalies. ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight’ is the first example in his discography. It was as if, having written the greatest protest songs of the American 20th century, revolutionising pop music in the process, Dylan said, ‘I may as well write a country classic now’.

Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right

6.

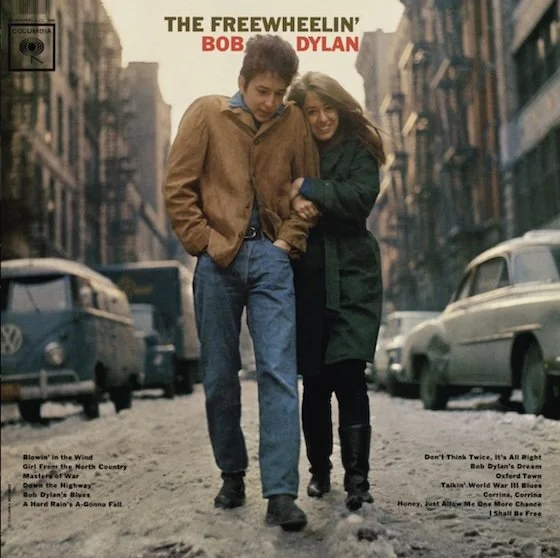

from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan

Dylan's first great love, Suze Rotolo, described hearing songs he’d written about her on the radio. It was ‘very flattering’, she said, and ‘very strange’. During her time in Italy between May and December 1962, Dylan called her often, but rarely mentioned his rapidly blossoming fame in New York. ‘When I came back he was getting really big,’ she told Dylan biographer Robert Shelton. Written during their transatlantic separation, when their relationship was under strain, it must have been extremely strange (and not entirely flattering) to hear ‘Don't Think Twice, It's All Right’. Dylan conceals his pain under a guise of indifference: ‘I ain't a-saying you treated me unkind / You could've done better but I don't mind’. Beneath the poetry, we can hear a hurt young man’s petulance: ‘I give her my heart, but she wanted my soul’.

Dylan might have left a clue in the song to ensure Suze knew it was about her. In her memoir, she describes returning home with Bob early one morning and hearing a rooster sing in the middle of New York City. It is the kind of small private moment lovers remember. But in ‘Don't Think Twice, It's All Right’ Dylan seems to have repurposed it: ‘When your rooster crows at the break of dawn / Look out your window and I'll be gone’. The lines transform a once romantic memory into a signal that their relationship has ended. Whenever Suze first heard the song, it must have left a bitter sting.

The second and final part of our ranking, Bob Dylan's Greatest Love Songs, will be published on 21 February.

© 2026 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

TAGS

RELATED

ANNIVERSARY ALBUM REVIEW

17 January 2026

22 November 2025

25 October 2025