Live Aid at 40: The story of a punk, a prime minister and a Britain now vanished (Part 1)

LIVE AID AT 40

The extraordinary story of Live Aid recalls a very different Britain, which came together to help a faraway African nation. It is difficult to imagine the same thing happening today.

20 December, 2025

Photo: LANDMARK MEDIA / Alamy

Davidwr

Photo: still from Twentieth Century Fox movie: Bohemian Rhapsody (2018)

‘It is 12 noon in London, 7:00 AM in Philadelphia and around the world it is time for Live Aid.’

Even before the stadium announcement had finished echoing around a sun-drenched Wembley, the white noise of the 72,000-strong crowd had erupted into a cacophony. Having paid a then exorbitant £25 for a ticket, people had been waiting on the tarpaulin-covered turf exposed to the hot sun for two hours. Overhead helicopters had been swarming, taxiing Elton John, Status Quo and Noel Edmonds to the venue over London’s gridlocked traffic. Backstage, crackling walkie-talkies attempted to make sense of the chaos, and BBC presenters including Andy Kershaw and Janice Long waited nervously for a live broadcast scheduled to last ten hours.

After the Coldstream Guards had played the opening of ‘God Save the Queen’, Status Quo took to the stage and launched into the 12-bar banger ‘Rockin' All Over the World’. Broadcast by satellite in more than 150 countries across the globe, including those behind the Iron Curtain, ‘Rockin' All Over the World’ was a fairly apt opener. Watching from the Royal Box Prince Charles turned to Bob Geldof to ask who was playing on stage. In his apparent confusion and grey suit he looked like a local businessman who had got lost on his way to a conference. Geldof explained, Prince Charles looked none the wiser and volunteers manning the 300 BBC phone lines began taking calls as donations started to trickle in.

The 13th of July 1985 was typical of a live summer television broadcast in Britain in the late 20th century, when most windows in the country opened, and the same tinny sounds from televisions floated out on the breeze. During the month of Wimbledon it was the thwok…thwok sound of a rally, punctuated by the polite static of applause. During FA Cup finals it was the commentary of the BBC’s John Motson set against the roar of the Wembley crowd. On that baking hot day in 1985, it was the pub-rock of Status Quo which came from tower blocks, council estates and suburban semis.

It was one of those moments when television drew most of the country around it at the same time, creating a nationwide communal experience. The 1966 World Cup final between England and West Germany had been watched by more than 32 million people. A year later Miss World generated an audience of nearly 24 million, and viewing figures for the 1981 wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana reached more than 28 million. On large TVs with buttons for preset channels and rooftop aerials, Live Aid was watched by more than 24 million.

“In a farcical muddle the television cameras turned on Sting and Simon Le Bon during George Michael's lines and Paul Weller during Bono’s. Some of the stars chatted to one another during the performance, and Bob Geldof rubbed his eye looking like he needed a nap after his Christmas dinner.”

Cigarette smoke drifted in the draught from front doors left on the latch, and hung over hi-fi stereo stack systems housed in upright glass-fronted cabinets. People were recording the live event on video cassette recorders, or VCRs, to be watched again and again whenever they wished to, albeit with a hazy picture which juddered when the pause button was pressed. In approximately 3 million of these homes, there would have been the same 7-inch single. Designed by Peter Blake, the British pop artist who co-created the cover for the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, the cover of 'Do They Know It's Christmas’ showed a montage of British Christmases through history: from Victorian parents with their children by the fireside to a 1930s mother kneeling beside her son as he plays with toy bricks. Foregrounded was a stark black-and-white photo cutout of two fly-covered Ethiopian children, reduced almost to skeletons by the famine which took place there in 1984 and 1985.

Televised in October 1984 BBC journalist Michael Buerk’s report on the ‘biblical’ famine in Ethiopia ranks amongst the most harrowing and consequential in British TV history. Millions watched thousands of dusty, emaciated Ethiopians beneath the unrelenting sun, starving adults and children packed into sheds and corpses covered in blankets or wrapped in sackcloths. One of those watching was Bob Geldof, lead singer of the Boomtown Rats. His band had moved on from the garage rock sound of their earliest recordings, but in attitude Geldof remained very much the foul-mouthed punk. It was that irreverent, can-do spirit which helped Geldof pull off his extraordinary achievements over the coming months. After watching Michael Buerk’s report, Geldof picked up a pen and scribbled down the lyrics to what would become ‘Do They Know It's Christmas’.

To record the song, Geldof recruited some of the biggest names in British pop music, including Bono, George Michael and Paul Young. Contributing to the spoken messages on the B-side, there were David Bowie and Paul McCartney. The hurriedly thrown-together music video eschewed any trace of the famine in Ethiopia, showing instead candid footage of the superstar musicians recording, standing in front of microphones reading the lyrics they hadn't had time to learn. The camera cut away to Phil Collins on the drums, Midge Ure behind the mixing desk and Bananarama arriving at the studio. The song became the fastest-selling UK single of all time, entering the chart in the top spot and becoming 1984's Christmas number one.

On Christmas Day of that year, after Noel Edmonds Live Live Christmas Breakfast Show and immediately before the Queen's Christmas Message at 3 o’clock, BBC One broadcast the Top of the Pops Christmas Special. Families across the country sat down in front of the TV after their Christmas lunch to watch members of Band-Aid mime the song. British Christmas number ones in the 1980s included St. Winifred's School Choir’s 'There's No One Quite Like Grandma', Shakin' Stevens’ ‘Merry Christmas Everyone’ and Cliff Richard’s ‘Mistletoe and Wine’. In 1984, it was something far more sobering. Opening with a repeated chime, conflating the sound of a Christmas church with a warning bell, the song sets off with an ominously shuffling drumbeat. Millions of Britons listened to the plea in the lyrics, made with a particularly British sense of politeness. We know you are enjoying yourself at Christmas, the song acknowledged, but please do spare a thought if you can for those starving in Ethiopia. In a farcical muddle the television cameras turned on Sting and Simon Le Bon during George Michael's lines and Paul Weller during Bono’s. Some of the stars chatted to one another during the performance, and Bob Geldof rubbed his eye looking like he needed a nap after his Christmas dinner. But none of it mattered. The collective star power felt uniquely special and, combined with the Christmas goodwill and charity feel-good factor, it felt like Band-Aid really were going to save Ethiopia, all whilst everyone in Britain still had a lovely Christmas.

“As the whole of Wembley Stadium did the double handclap during the chorus of Queen’s ‘Radio Ga Ga’, Mercury looked back at the audience having already experienced symptoms associated with HIV.”

Wind forward to the following summer at Wembley and the greatest pop stars of the day (and some of the greatest in history) kept coming. It was an embarrassment of riches and wardrobe choices. Mullets abounded. Nik Kershaw had one, Bono’s sported blonde highlights and Howard Jones’ was so huge it looked like giant birds had built a nest on his head. There were shiny emerald green suits, Mark Knopfler of Dire Straits was wearing the same headband as American tennis star John McEnroe, and when he came on stage Sting looked like he was still in his pyjamas.

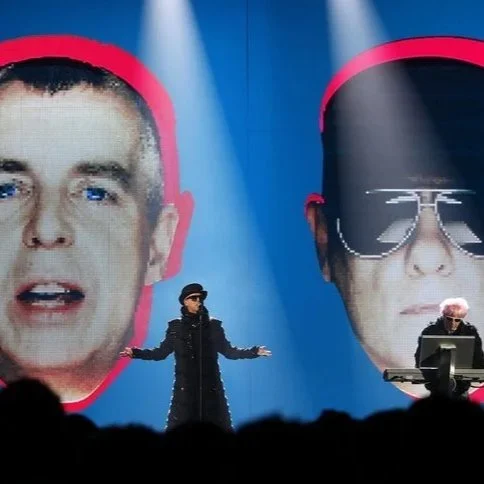

Meanwhile backstage some of the darker themes of the decade were playing out. Behind the charismatic flamboyance of his performance, Queen’s Freddie Mercury was hiding in plain sight. That the singer was gay was an open secret. Almost 20 years after the Sexual Offences Act was passed, which decriminalised sex between men over the age of 21, gay rights in Britain would suffer a major setback when Section 28 was enacted in May 1988, prohibiting local authorities from promoting homosexuality. Margaret Thatcher commented: ‘Children who need to be taught to respect traditional moral values are being taught that they have an inalienable right to be gay. All of those children are being cheated of a sound start in life’. Section 28 sent a wrecking ball through the gay community. When homophobic bullying took place at schools, teachers felt unable to step in or talk about it. Due to a general perception that members of Culture Club and Pet Shop Boys were gay, one former pupil remembered their music being banned from school discos.

As the whole of Wembley Stadium did the double handclap during the chorus of Queen’s ‘Radio Ga Ga’, Mercury looked back at the audience having already experienced symptoms associated with HIV. In the late 1980s British tabloids relentlessly speculated whether Mercury had HIV, until in 1991 the singer finally announced he had tested positive. Having attended Live Aid, Princess Diana would go on less than two years later to open Britain's pioneering HIV/AIDS unit at Middlesex Hospital. Just as importantly, her public hugging of those with HIV did much to dispel the fear and ignorance surrounding the virus.

© 2025 State of Sound. All Rights Reserved

FEATURE

27 December 2025

MORE ON THE 1980s

PET SHOP BOYS

15 November 2025

MORE FEATURES

25 October 2025